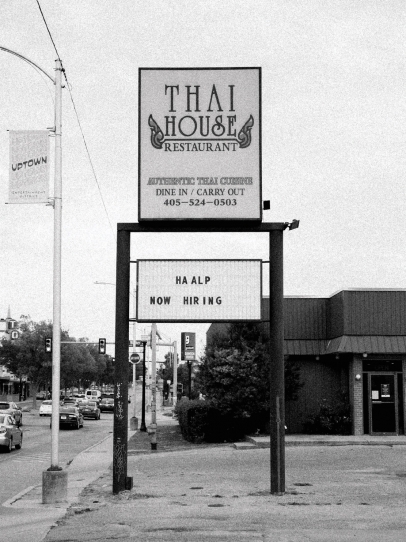

Where Have All the Workers Gone?

As customers return, some workers have chosen to leave

Jazz Rodriguez started bartending after all of the employees at the establishment where he worked quit. After leveraging his position as a bartender across the city, he eventually worked his way to becoming a bar manager at what he described as a trendy cocktail bar located in downtown Oklahoma City. When the pandemic occurred, he did what he could to sustain a living wage by making take-home cocktail kits and selling pre-made frozen drinks to friends through direct messages on Instagram. Then, one day, he also decided to quit.

Rodriguez was one of 174,200 employees staffed in the leisure or hospitality industry across Oklahoma in 2019, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor statistics. Staffing levels have yet to return to their pre-pandemic numbers; 165,000 people were employed in leisure and hospitality in 2021, a 5.2% decline.

Rodriguez says he felt he had gone as far as he could in bar management. In a moment of self-reflection during the pandemic, he says he realized how toxic his work environment was. “At some point, the bar shifted from a place to connect and fulfill the need for creative expression to essentially a slow-motion mental health crisis,” he said.

During this time, Rodriguez coped by abusing alcohol to escape from the pressures of what he referred to as an “increasingly perilous and demanding” industry.

“What seemed like a party sometimes was actually more akin to a train wreck or an emotional breakdown,” he said.

Due to the mental load and physical work in the Oklahoma City service industry, he chose to leave to start his own alcoholic beverage business. As restaurants have reopened post-pandemic, those still working in the service industry voiced similar concerns about conditions in the workplace.

Aly Cunningham, owner of Happy Plate Concepts, believes the service industry is a tough place whether during a pandemic or otherwise, but the pivot in how establishments were run forced those in charge to be creative and focus on what mattered to workers.

“To me, the service industry feels more aware of mental wellness, quality of life, and fair wages. All of that is never a bad thing, but I would have preferred it all to be under different circumstances,” she said. Cunningham believes those workers choosing not to return are prioritizing their health instead of feeling obligated to work to pay their bills. “If a business can’t take care of their teams, they shouldn’t be in business,” she said. “Did we really need a pandemic to be able to say, ‘You’re sick, stay home, we’ll make sure you’re not going to miss out on pay?’”

Cunningham says the pandemic made many workers push through fatigue, or stay in a constant state of alert due to health and safety standards such as checking temperatures, sanitation, and washing hands. “That’s not a new thing, but knowing how high the stakes are, it’s about life and death, performing, under those circumstances, can wear you down,” she said.

Karrie Evans, an assistant food and beverage director at a hotel, cites the post-pandemic attitude of people in general as what is grinding workers to the point of exhaustion. “Everyone’s walking around with a shorter fuse and less empathy toward one another. They are less gracious for the most part and, for many of us, we just don’t care to put up with angry guests anymore,” she said. When Evans was furloughed during the pandemic for six months, she worked as a bartender and checked IDs to assist a local bar she liked because they could not find enough people to cover shifts.

Despite establishments constantly looking to hire to cover shifts or other duties, some workers are choosing not to return because, in Evans’ opinion, “The service industry is no longer this super amazing, really cool, reality show kind of gig anymore.”

Evans believes those workers reevaluated their priorities, ranging from pursuing other opportunities in life to the toll working in the service industry can take on a person’s health, such as in the instance of Rodriguez. “This is my chance to do something that I feel good about that brings me joy and happiness. Money may not be much, but I have more flexibility, I can focus on my mental health, my family, and all these priorities that get pushed to the side when you’re working every Thursday, Friday, and Saturday night,” she said.

Rodriguez has managed to care for himself while still maintaining a connection to the service industry, but he suggests some workers will continue to reevaluate their priorities. “Without the passion for hospitality keeping you coming to work, there seems to be less and less reason to clock in these days.”